The Stray Kernels blog has moved! With the launch of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s new CONNECTIONS website, Stray Kernels can now be found at http://cultivateconnections.org/stray-kernels/ Come on over to read more random musings and kernels of wisdom!

Posted in agriculture, Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

I like being right, and it irritates people sometimes. (Just ask my husband.)

If I hear a factual inaccuracy on a topic I know well, I have to bite my tongue not to correct it. Maybe it’s because I’m an educator at my core. I want folks to base their beliefs and behaviors on facts.

But facts—things that are known, proven, and verifiable—don’t really matter.

Are you bristling right now? Are you thinking, “You’re wrong. They matter to me!” Hear me out.

How we feel always triumphs over the facts with which we are presented. Don’t believe me? How do you feel about GMOs? Vaccines? Climate change? Immigration? Breast feeding vs. formula? Nuclear energy? Motorcycle helmets? Pesticides? Politics? Have I hit any of your hot buttons yet? What’s running through your mind right now? Is your blood pressure more elevated than when you started reading this paragraph? How do you feel?

Now, pick a topic listed above that you feel strongly about. Search for websites you would recommend to others wishing to learn about it. What did you find? Did what you found support what you believe? Did you start reading a site and quickly close it because you knew it was wrong? How did you know it was wrong? Did you find a site that changed your mind?

Recently I had a long, heated discussion with a friend. Let’s call him Ken. Our conversation started on the topic of vaccines and quickly veered into agriculture. We talked late into the night, until I was trembling from the effort of balancing facts, feelings, and friendship.

Ken believes farmers are powerless victims of corporate control and ownership. He believes one seed company controls the government agencies that regulate our food supply. He thinks livestock are “crammed together” and treated cruelly for profit. He believes farmers grow corn to receive subsidies but he feels it’s not nutritious so they should grow something else instead.

My friend is intelligent and passionate, and like most people in our country, far removed from production agriculture. As we talked, the words “Facts don’t matter; feelings do” kept running through my mind, along with “Ken and his wife are our friends, and I want them to remain so after this dialog.”

It was like I was having two separate conversations. One out loud with Ken, and one internally, with myself. I reminded myself that Ken is a Marine, and—like my own husband—a disabled veteran. As we talked about the credibility of the CDC, FDA, and EPA, I remembered that many veterans have justifiable reasons to distrust government agencies as a result of their experiences with the DoD and VA.

I remembered the “backfire effect,” a recent research finding which revealed that people with strongly-held beliefs tend to cling to them even more tightly when presented with evidence to the contrary. I counseled myself to ask thoughtful questions about Ken’s beliefs instead of launching facts at him to “prove him wrong.”

At many points in the conversation, I thought of simply cutting it short by telling Ken I was tired and ready for bed. I was tempted to give up and write him off as misinformed and crazy. But, while he may have absorbed misinformation, he’s not crazy. I knew that to shrug him off as such would just widen the division we’re all experiencing now.

When the conversation ended, he thanked me for opening his eyes to new things to think about. I thanked him for challenging me.

In the end, I’m not sure I convinced him of anything. If I truly did open his eyes to new information, it wasn’t because I hurled facts at him. Hopefully it was because I tried to show how I felt, and that I cared about his beliefs even when I didn’t agree with them.

When I say facts don’t matter, what I really mean is facts don’t matter unless you acknowledge feelings first. If you skip that step, facts really don’t matter, because they won’t make a difference in what people believe.

As the saying goes: People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the September-October 2017 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in communication, misconceptions | Leave a Comment »

I constantly long to be connected to nature.

When was the last time you sat in the soil, strolled through a forest, or splashed in a stream? How many birds have you taken the time to listen to today?

If you’re like me, you long to do these things but rarely have time. Days go by when my feet touch only asphalt, concrete, or flooring, and my ears note only engines, voices, and HVAC systems. We’ve structured our human lives to mostly separate ourselves from nature; from dirt, discomfort, and inconvenience. In his book “Last Child in the Woods,” author Richard Louv introduced the term “nature-deficit disorder” to describe the often-unrecognized disconnect—the unanswered longing to experience nature—that results.

When farmers lament, “Kids these days just don’t know where their food comes from,” I believe they are describing a consequence of this disconnect. After all, what is agriculture but the intersection of humans and nature to produce food? Those who engage in food production are closer to nature on a daily basis than most of us. Outside of agriculture, kids (and many adults) these days don’t know where their food comes from.

Is this “natural” ketchup safer or healthier than other brands?

I believe that another symptom of this disconnect is our insatiable drive for “natural” things. Walk the aisles of a grocery store, browse personal care items on Amazon, or scroll through posts on Facebook and you’ll see hundreds of examples. It’s as though we know deep down we need to stay connected to nature, so instead of a walk on the prairie we don’t have time for, we reach for Nature Made® Echinacea supplements.

Nature is beautiful. Nature is essential. Nature is necessary for our survival.

But.

Repeat after me: “Natural” doesn’t always mean “safe.”

I used to say I’d rather consume a substance produced by a plant than one developed in a lab. I remember the pleasurable little rush of self-righteousness I got from saying so out loud. “Natural” meant green plants waving their leaves against a sunny blue sky, not unidentifiable people wearing lab coats and goggles against a backdrop of fluorescent lights and stainless steel.

Then I started following credible science and agriculture organizations online. Whether discussing food ingredients, crop production, or medical advances, the topic of whether “natural” equates to “safe” comes up repeatedly. And what the science keeps pointing out is that “natural” things are often very dangerous.

Take apricot seed kernels. Aside from the fact that they are rock-hard and not very tasty, there’s a doggone good reason we don’t eat cherry, peach, or apricot pits. They contain a chemical compound called amygdalin, which, when eaten, releases cyanide—a poison. Search online for apricot kernels, though, and you’ll find dozens of retailers selling them and many articles touting their use as a cancer treatment. Supposedly, cyanide kills cancer cells. Maybe it does, but in doing so it may kill you as well. Nevertheless, because it grew on a tree and is “natural,” it must be safer (some think) than chemotherapy, which seems decidedly unnatural. Scientific evidence shows that apricot kernels are not safe, but the belief persists.

The quest for apricot kernels is an extreme example of a logical fallacy known as “appeal to nature,” or the argument that “natural” things are good, therefore “unnatural” things are bad. It is so convincing that we see it constantly in product marketing. Food manufacturers advertise the replacement of “artificial” flavorings and colorings with “natural” ones. Genetic modification is perceived as unnatural, so the Non-GMO Project seal now appears on thousands of products from cinnamon to sea salt despite there being only ten commercially-available GMO crops. Organic production prohibits the use of most synthetic fertilizers and crop protectants, so consumers assume foods labeled “organic” are natural and thus safer. It’s increasingly difficult to find a package label that doesn’t include the word “natural” or “nature.”

And yet (repeat after me), “natural” doesn’t always mean “safe.” Whether or not something is natural is irrelevant to its safety. Many natural things are amazing, even life-saving. Some will kill you. The same is true of synthetic, “unnatural” things. Toilets, toothbrushes, and trucks are not natural, yet they improve our lives. Safety hinges not on whether a substance is natural or synthetic, but on how much of the substance you are exposed to. Drinking too much clean, pure (natural) water can kill you. So can a truck.

By all means, get back to nature. But remember, “natural” doesn’t always mean “safe.” Anyone who tells you otherwise is trying to sell you something.

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the August 2017 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in agriculture, food safety, misconceptions | Leave a Comment »

I’ve been thinking.

What if there was a thing that could be produced not just for food, but for hundreds of other products, too?

What if that thing could be easily propagated and collected? What if it didn’t spoil easily so it could be stored for long periods of time and shipped around the country or around the world with no refrigeration and minimum waste? What if the size, shape, and density of that thing made it easy to design efficient containers and conveyances to store and move it?

What if, at a moment’s notice, that thing could be used for food or renewable energy, depending on what was needed most? Better yet, what if it could be used for both simultaneously? What if you could break that thing into various components and thus make food for protein-producing livestock and clean-burning fuel for cars at the same time?

What if that thing were a plant? What if it could be adapted to be grown almost anywhere, in a wide range of soils and climates? What if scientists could continuously tweak this plant so it could yield more on less land with less water, less fertilizer, and fewer pesticides?

What if, while it was growing, the plant would produce ample amounts of oxygen while removing tons of carbon dioxide from the air? What if farmers could experiment with their growing techniques for this plant to minimize soil erosion, water pollution, fuel use, and emissions?

Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

What if I told you this thing—this plant—already exists? It does, and chances are that if you live in the U.S., there’s a field of it within a few miles of where you’re sitting. It’s the #1 crop grown in our state and our nation. It’s corn.

So, what was it that got me thinking so hard about corn?

Every year, one day of the National Ag in the Classroom Conference features tours of agricultural sites. This is usually my favorite part of the conference, because I get to experience facets of U.S. agriculture I’ve never seen in person. I’ve sweated in the hot sun of a sugar cane field in Louisiana, inhaled the fruity aroma inside a tart cherry processing facility in Utah, and squinted across the dusty pens of a sheep feedlot in Colorado.

This year’s conference was in Kansas City, Missouri. Of the seven tour choices offered, I settled on the one named “Corn is King!” Practically every ag literacy program I coordinate touches on corn in some way, so I figured it wouldn’t hurt to learn more about it.

It was incredible to see the engineering behind how starches are derived from corn.

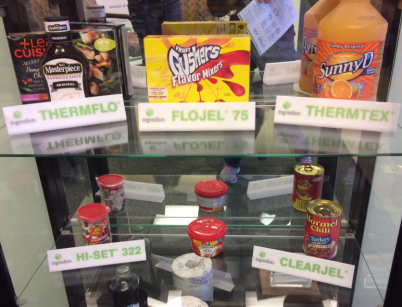

The tour was of an Ingredion processing facility where they make several kinds of modified starch. You’ve probably seen “modified cornstarch” or “modified food starch” in the ingredients lists of various food products. (The term “modified” refers to the starch having been physically or chemically treated to enhance its properties as a thickener, emulsifier, or other use.) When you run across modified starch it was probably made in the facility I visited, as it produces about 70% of the modified starch used in the U.S.

The Ingredion facility reminded me of an enormous boiler room, with its huge steel tanks, labyrinth of pipes, hissing steam, rumbling machines, and random puddles on the cement floor. I’ve always hated boiler rooms. So as I tried to hear our tour guide while ignoring the hissing and rumbling, I thought deeply about corn.

This is just a tiny sampling of products containing modified starches to improve stability and texture.

You’ve probably heard from critics who say that corn’s dominating presence in our grocery stores is a bad thing. That it’s part of a giant, greedy conspiracy whose players include farmers, food manufacturers, and the government. I’m anything but an expert on the incentives and economics that play into corn production and use. But my feeling is that for all the reasons I listed in my “what ifs” earlier, corn is amazing. Rather than disturbing me, I find it miraculous that within just a few hours of my day, corn fuels my car, makes my paper smooth, keeps my pudding creamy, and feeds the pigs that make my bacon.

Corn IS king!

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the July 2017 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in agriculture, corn | Leave a Comment »

These words have been running through my head for a few days, for a variety of unrelated reasons. One is that I’ve been practicing a version of a song by that title with our church choir. Another is that the early signs of spring remind me that the warmer, greener days of our annual circle around the sun are quickly approaching.

Yet another reason I’ve been pondering these words is that I recently attended the visitation of a friend’s mother. If you know the hymn’s lyrics (can you hear it in your mind in Johnny Cash’s voice?), you might remember that it’s about sorrow at a mother’s death.

But the main reason these words have relevance to me lately seems unrelated to death and loss. In this case, it’s about the circle of people who help us each year with our Ag in the Classroom program. As I was conducting the volunteer training back in January, it dawned on me that today we have volunteers who experienced the Ag in the Classroom presentations when they were in elementary school. Now they’re back as young adults, sharing with elementary students the experiences they themselves had in school.

Travis Hughes remembers Ag in the Classroom volunteers visiting his elementary school classroom when he was younger. This year he paid it forward by volunteering himself.

Travis Hughes is one of those. It’s probably no surprise that making ice cream in second grade is the Ag in the Classroom experience he remembers best. He remembers how excited he was to receive his certificate of participation, and how the volunteer presenter made him and his classmates feel special and appreciated. This year, Travis was paying it forward as he delivered fourth grade “Mapping Illinois Agriculture” presentations in three classrooms. After his presentations, he shared with me how much he enjoyed it, and how he “gets” the kids who were a little unruly during his lessons, because he knows there were times he was like that, too.

To me, what’s striking about “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” is that the lyrics are sad, but the song isn’t. The song, when sung, is hopeful. The answer is yes, the circle will stay intact. Spring will come back after the dark days of winter. Mothers and fathers will grow old and pass on but their children will grow up and have children of their own. Elementary school kids will experience Ag in the Classroom lessons and some will become Ag in the Classroom volunteers themselves.

When I asked if he could remember who visited his second grade classroom to give the Ag in the Classroom presentation, Travis said he couldn’t. Considering he was only 7 or 8 at the time, I cut him some slack. But I was curious, so I looked it up in my files. Travis was in second grade in 2003, and he says his teacher at Davenport Elementary was Mrs. Sue Finney. That year, Genoa-area farmer Don Bray conducted the “From Cow to Ice Cream” lesson in Mrs. Finney’s room.

Genoa-area farmer Don Bray (center) was an Ag in the Classroom volunteer and Ag Literacy Committee member for many years.

Don presented dozens of “From Cow to Ice Cream” lessons over many years, all the way up to February of 2011. In the summer of that same year, Don died. Today, Travis Hughes still remembers that he learned about dairy farming and made ice cream in second grade. He still recalls how special that Ag in the Classroom volunteer—Don Bray—made him feel.

Thanks to people like Don, Travis, and well over 100 individuals who volunteer for Ag in the Classroom in our county each year, the circle is indeed unbroken.

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the March 2017 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in agricultural literacy, agriculture, volunteering | Leave a Comment »

It has begun!

I realized recently that it’s not the sights of spring that make me happiest. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the bursting buds, greening grass, or dancing daffodils. I do. But it’s the sounds that make my heart really sing in the spring.

It’s usually a chilly, gray morning sometime in March when I first hear “kronk-a-REEEEE!” I’ll look around in surprise, and there he will be, high in a tree—a red-winged blackbird. The males migrate first, I learned as a child. They start staking out territories as they wait for soon-to-arrive females. If you’re traveling the interstate, watch the grassy roadsides and you’ll see one male here on a fence post, and an eighth of a mile or so later, another one there in a small tree. And then another, and another. Roll down the window as you pass and you’ll hear them informing all passers-by of their territorial boundaries. “Kronk-a-REEEEE!”

Photo © Johnathan Nightingale

As the mornings begin to brighten earlier, I notice a sound upon waking that’s difficult to hear, muffled by still-closed windows. But robins are persistent and loud, and their early morning voices penetrate glass. “Cheerio-cheerio-cheep-a-cheep-cheerio…” (Later in the season, the robins and other birds will create an impossible-to-ignore 4 a.m. cacophony.) Robins may be the most well-known herald of spring in our latitude, but my bird expert friends tell me some robins stick around all winter, foraging for berries in wandering flocks which stay mostly hidden from human view.

Thunder is a spring sound, too. I think of it as mostly an evening and nighttime sound. It may seem fanciful, but I’m convinced I can feel thunder well before it can actually be heard. Stormy spring evenings just seem to vibrate long before they rumble and flash. Of course, thunder is eventually accompanied by the racket of rain and wind, too. And you really know it’s a doozy of a spring storm when hail clatters against the windows and roof.

When spring storms leave ponds in patches of woodland and edges of fields, another bunch of critters makes themselves heard. The first time I hear them each year, it stops me in my tracks in delight. “Spring peepers!” I will exclaim out loud, even if I am alone. (I probably look a little bit batty when I do this.) For a creature about as big around as a quarter, a spring peeper can make an enormous noise. Its call is a piercingly high-pitched “preep, preep, preep,” but I’ve almost never heard just one at a time. Spring peepers are a species of chorus frog, thus they sing in deafening gangs. Stand near a swampy spot in early April, and the peepers will make your eardrums throb. Move too quickly or loudly, however, and they all fall silent.

Later in spring, when it’s warm enough to leave a bedroom window open overnight, yet another animal makes its presence known. Yipping and yowling, coyotes call across the open fields. After lifting my head from the pillow to confirm that our two dogs are, in fact, safely in the house, I relax and listen until the coyote concert ends. While I know many a 4-H poultry project comes to an untimely end in the jaws of these pesky predators, I can’t help but enjoy their wild, brief serenade.

Photo © DeKalb County Farm Bureau

Open-window, dry spring days bring another auditory treat I treasure. Caused by neither a creature nor a weather phenomenon, this sound nevertheless seems to belong to the natural landscape of northern Illinois. It’s the sound of a distant tractor as it pulls a planter across the field. When the weather is right, the hum of planting continues through the day and into the night, when I fall asleep listening to the sound of another growing season beginning.

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the April-May 2017 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

“Volunteering is the ultimate exercise in democracy. You vote in elections once a year, but when you volunteer, you vote every day about the kind of community you want to live in.” ~ Unknown

“Volunteering is the ultimate exercise in democracy. You vote in elections once a year, but when you volunteer, you vote every day about the kind of community you want to live in.” ~ Unknown

This wisdom has been running through my mind a lot lately. And not just because of our currently heated national conversation on what kind of a country we want to live in. It’s also because of something that’s been taking place right here at DeKalb County Farm Bureau, something that takes place every year at this time.

That “something” is our Ag in the Classroom program for first through fourth grades. As I write this, I’m in the midst of an ongoing give-and-take with dozens of volunteers—people who are “voting” right now about the kind of community in which they want to live. By volunteering to deliver Ag in the Classroom presentations, I believe they are voting for DeKalb County to be the kind of community where:

- Students and teachers understand why farming matters.

- Farmers and others who work in agriculture are valued for their contribution to society.

- Consumers can go to the grocery store and feel a personal connection to someone who produces the food they buy.

- The agricultural community cares about the education and well-being of all our children.

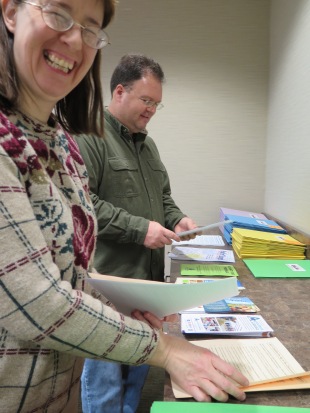

It’s not just the classroom volunteers who are voting to shape our community. It’s the retired Ag Literacy Committee members who call me to say, “What can I do?”—and then spend an entire afternoon in my office labeling teacher thank-you gifts and gift bags. It’s the Ag Literacy Committee spending an evening counting, bundling, stuffing, and labeling—all while discussing other ways to increase agricultural understanding in our county and beyond. And it’s also the teachers who reserve precious classroom time to focus on agriculture.

It’s not just the classroom volunteers who are voting to shape our community. It’s the retired Ag Literacy Committee members who call me to say, “What can I do?”—and then spend an entire afternoon in my office labeling teacher thank-you gifts and gift bags. It’s the Ag Literacy Committee spending an evening counting, bundling, stuffing, and labeling—all while discussing other ways to increase agricultural understanding in our county and beyond. And it’s also the teachers who reserve precious classroom time to focus on agriculture.

I never feel as though I adequately thank these individuals for the time and energy they devote to Ag in the Classroom. I try, though. I love it when I can catch volunteers returning supplies after their presentations. That’s when I can say “thank you” in person, and hear stories about their classroom visits.

I often hear that both students AND teachers learn surprising new facts from the lessons. “The kids thought the ear of popcorn was Indian corn,” volunteers will say, or “The teacher said she hadn’t realized that hand sanitizer is made with ethanol from corn.”

By the end of this month, over 100 people in our county will exercise democracy by volunteering for Ag in the Classroom. I know they’re busy, but they step forward and take the time to do so anyway. For that, I am grateful.

“Volunteers do not necessarily have the time; they just have the heart.” ~ Elizabeth Andrew

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the February 2017 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in agricultural literacy, agriculture, volunteering | Leave a Comment »

Grandma’s Christmas tree was always covered in gold. Gold tinsel, gold ornaments, and gold lights. I don’t know where she and Grandpa found all-gold Christmas lights (deep yellow, really), and I wonder if my memory is playing tricks on me. But I swear they were gold.

Grandma’s Christmas tree was always covered in gold. Gold tinsel, gold ornaments, and gold lights. I don’t know where she and Grandpa found all-gold Christmas lights (deep yellow, really), and I wonder if my memory is playing tricks on me. But I swear they were gold.

It was a fairly large tree, but it wasn’t big enough to shelter all the gifts for over a dozen grandchildren and all my aunts and uncles. In my mind’s eye, once everyone in the family had arrived and added their gifts, it was physically impossible to even reach the tree. The gifts occupied almost half of the living room, in a riot of tantalizing colors, shapes, and sizes.

A nativity scene was always located at the other end of the living room, next to Grandpas’ recliner. Grandma would set it up on a small table—I think maybe it was a TV tray table—so that it was just the right height for us cousins to rearrange baby Jesus and his entourage.

Perhaps even more inviting for us than playing with the crèche, however, was the basket of homemade red and green popcorn balls that Grandma made and placed under the little table. We were told (perhaps to stave off any thoughts of being greedy) that there were enough for every cousin to have just one. I can still remember the exact flavor of those popcorn balls, and the way I’d spend an hour or so undoubtedly making strange faces as I used my tongue to pry the chewy, gooey fragments out of my molars.

The farmhouse would be bursting with people and noise. In her small kitchen, Grandma and my aunts would elbow past one another, arranging dishes on the counter. Every so often, an uncle would appear, carrying another “dish to pass” from the car. His glasses (I think all my uncles wore glasses) would be foggy from the sudden transition from the icy outdoors to indoor warmth, and his coat would be stiff and radiating cold air. “Where would you like this?” he would say, and Grandma would rearrange the counter to make room.

I suppose every family has trademark dishes that are a prerequisite for a complete holiday experience. Two stand out most vividly in my memory. The first is Grandma’s deviled eggs. My grandparents had an egg farm, and deviled eggs were Grandma’s specialty. Hers were sprinkled with paprika, decorated with sliced olives, and contained just a hint of sweetness amidst their savory eggy-ness.

The other dish I remember well is a dessert everyone referred to as “Gap ‘n Swallow.” It was a creamy, pink, fluffy treat served in squares cut from a cake pan. As far as I know, it was simply a chilled mixture of vanilla ice cream and red Jell-o. When it came time for dessert, it was a light and jiggly accompaniment to the cookies, brownies, and Christmas-decorated ice cream squares which were also traditional to our family gatherings.

Although he’s been gone for several years, I can still see Grandpa’s face and hear his voice clearly in my mind. His hair is fluffy and white, he’s wearing a red flannel shirt, and he shakes his head bemusedly as he says “Well, I’ll be darned.” I see him on his hands and knees near the Christmas tree, peering at labels as he passes out gifts.

Grandma is gone, too. But in my mind, her tiny frame is still crowned with brown hair in a “beehive” style. Though her hands shake slightly, she is seated at her piano playing “Willy Claus, Little Son of Santa Claus” for us.

I hope the ghosts of your holidays past are warm and happy memories.

Merry Christmas!

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the December 2016 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in family, memories | Leave a Comment »

Fall isn’t my favorite season.

There. I said it.

Many people proclaim their fondness for fall. I get it. There is much to appreciate: lower humidity, gorgeous colors, crisp mornings and even crisper apples. Of course autumn also brings the grandeur of harvest. On sunny fall afternoons, golden leaves dance in the air and combines roar across dusty fields. I yearn to stay outside, lifting my face to the sun, breathing deeply, soaking it in.

My perpetual struggle with fall is that no matter how glorious it is, I know how it ends.

It’s impossible to ignore the signs. Just outside my window is a bird’s nest. Last spring, I watched the endeavors of a motherly robin carrying grass and twigs to build it. As the tree’s leaves grew denser, I caught glimpses of Mama Robin as she nestled in, warming her eggs. By the time the eggs presumably hatched, fully-grown leaves obscured my view. Now that it is fall, the tree is nearly naked. There clings the empty nest, ragged and forlorn.

Parenting a young child involves a number of obligatory seasonal traditions to which one must adhere. In fall, that includes visiting a pumpkin patch, playing in leaves, and picking apples. To skip these activities is to ensure a nagging sense of guilt that you are shunning your parental duties.

Thus, one windy October Saturday found our little family in the midst of a friend’s enormous pumpkin patch. It was a struggle just getting there. Neither my husband nor my daughter felt well and consequently both were crabby. But I knew it was a now-or-never moment: If we didn’t go then, our schedules or the weather would prevent us from going at all. No pumpkin picking would mean no pumpkins, no pumpkins would mean no Jack-o-lantern carving—another skipped tradition. So we went.

Thus, one windy October Saturday found our little family in the midst of a friend’s enormous pumpkin patch. It was a struggle just getting there. Neither my husband nor my daughter felt well and consequently both were crabby. But I knew it was a now-or-never moment: If we didn’t go then, our schedules or the weather would prevent us from going at all. No pumpkin picking would mean no pumpkins, no pumpkins would mean no Jack-o-lantern carving—another skipped tradition. So we went.

It turned into a joyful treasure hunt. Nestled among shriveled vines was an assortment of pumpkin varieties, ranging from adorable orange fruits that fit in the palm of my hand to good-sized pumpkins our 3 year-old could barely move, much less carry. The three of us tramped to and fro, tripping over vines as we carried our treasures. Naya liked the “baby” pumpkins. I picked several medium-sized pumpkins to decorate our front steps. My husband chose some larger ones for carving.

Our next stop was to surprise my parents by scattering decorative pumpkins around their property: on their front porch, near the mailbox, at the base of a tree. After lunch, we checked off another fall ritual by picking apples in the orchard behind their old barn. Later, I would make homemade applesauce.

After 46 years, I’m still trying to come to grips with fall. On one hand, it saddens me because it signifies the end of so many things I love, like listening to katydids through open windows at night or reading on the front porch swing on sultry summer days. It’s the end of relaxing into warmth instead of bracing for cold, the end of wearing t-shirts and flip flops.

On the other hand, fall marks the magnificent culmination of another growing season. It’s the time when fields and forests yield their bountiful crops and beautiful leaves so that they may rest. I’ve often mused that the brightly-colored leaves of fall are God’s way of blasting us with beauty to carry us through the long, dark winter.

Despite the paradox that autumn presents, my heart knows it should be celebrated. Celebrations, after all, make difficult things bearable. Maybe that’s why seasonal traditions matter, even if at first we do them out of guilt. Picking pumpkins was a way of compelling myself to embrace and enjoy this season. Eating homemade applesauce from our freezer will remind me of fall’s bounty for months to come. For all of us, our Thanksgiving gatherings will be celebrations of another growing season, successful harvest, and family.

Besides, if there were no autumn and subsequent winter, there would be no spring.

And when spring returns, my robin will build another nest.

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the November 2016 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in agriculture | Leave a Comment »

She’s only 3½ years old. But my daughter is at the “why” stage and actively soaking up any and all information we have the patience to share with her. This, coupled with my job in ag literacy, prompted me to think about what I want her to know about agriculture at this age.

So here goes. Here are six things I want my child to learn about food and farming while she’s still young, and how I will explain each (if I haven’t already).

- Food doesn’t come from the grocery store. It comes from farms. I’ve explained to Naya that before food gets to the grocery store, farmers grow or raise it on farms. Then some things–like bread, applesauce, and bacon–go to processing plants to be made into the foods we eat. They are then shipped to the grocery store where we buy them to take home and eat.

- Farms are places where plants are grown or animals are raised for all of us to eat. It doesn’t make sense to say food comes from farms and not explain what a farm is. We also point out farms as we travel and talk about what might be grown or raised at each one.

- Farmers are the people who raise our food. I want my child to know that farmers are essential to our lives. Why? Because without them we would all have to grow our own food. Most of us don’t have the time, knowledge, or space to produce everything we eat.

- The fields around us aren’t just scenery; they are our food. I often call my daughter’s attention to the beauty around us. Our rural landscape of corn and soybeans is peaceful, open, and pretty. It’s also where some of our food comes from. I will explain to her that the plants growing in farmers’ fields are called crops.

My daughter, exploring a cornfield at the age of two. I want her to know that the field around us provide some of our food.

- Animals that farmers raise for food are called livestock. They are not pets. I want Naya to understand that pets and livestock serve different purposes. Pets like our two dogs are meant to be our companions, and livestock provide us with food. However, just because farm animals aren’t pets doesn’t mean humans don’t have a responsibility to keep them safe, healthy, and comfortable. Farmers provide their animals with special food, special places to live, and even special doctors–called veterinarians–just like we do for our pets. When the right moments arise, we will help her understand that everything living, people included, relies on other living things to survive. (One such moment recently presented itself when she caught a fish which hours later appeared as a fried filet on a plate. “Daddy,” she questioned, “where’d his head go?”)

- Chocolate milk doesn’t come from brown cows. I don’t know why adults persist in saying this. Some must think it’s funny, and a few apparently think it’s true. Either way, if you tell a little kid that chocolate milk comes from brown cows and don’t quickly explain that you’re just being silly, they will believe you. Unless they live on a dairy farm or someone has already told them otherwise, they don’t know any better. I want my daughter to know better. She doesn’t yet seem interested in chocolate milk, but when she is, we will explain that all cows give white milk, and humans add the chocolate later on.

As Naya continues to grow and ask “Why?” the information we can share with her will obviously become more complex and in-depth. But this seems like a good place to start.

What do YOU think a preschooler should know about agriculture?

This post also appeared as the “Stray Kernels” column in the Sept.-Oct. 2016 issue of DeKalb County Farm Bureau’s Connections magazine.

Posted in agricultural literacy, agriculture, farmers, farming | Leave a Comment »